Saltmarsh is a coastal ecosystem that performs a number of different roles. It supports biodiversity (such as nursery sites for commercial fish and shellfish, and feeding and nesting grounds for wading birds), stores carbon to mitigate against climate change, plays a valuable role in natural flood and coastal defence, helps improve water quality, and provides cultural, wellbeing and recreational benefits to people visiting the marshes.

Chichester Harbour is the seventh largest expanse of saltmarsh in the UK, but like many natural environments, it faces its own threats, both manmade and natural.

What is saltmarsh?

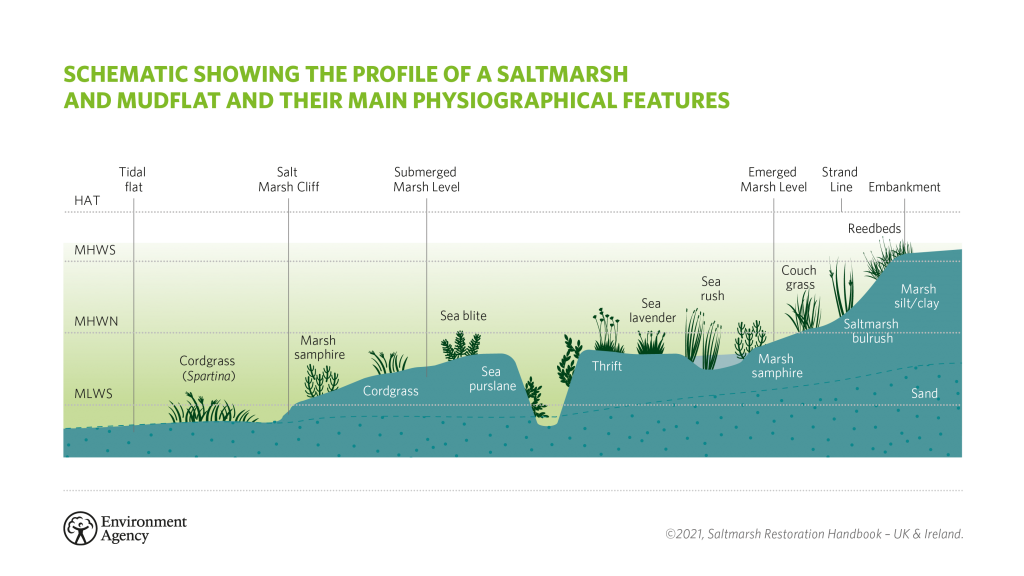

Saltmarsh is the intertidal area at the top of the mud flats and the immediate hinterland. The sea typically only reaches it at high tide, but the salt permeates the soil making it more attractive to different flora and fauna than traditional marsh or grassland. Saltmarsh is created when sediment builds on top of existing mudflats, rising above the mean high-water mark, allowing plants to seed and take root. These plants thrive in salty conditions with some able to be inundated with each tide and others, further towards land, enjoying the saline conditions.

Many plants growing on saltmarsh are not found anywhere else, creating a unique environment which is important for small creatures such as worms, shrimps and shellfish. These in turn attract wading birds and wildfowl.

As plants arrive and grow, their roots help to stick the mud particles together and trap even more sediment, creating stability. Over time, this process creates blocks of flat, low growing vegetation with narrow channels between. These channels provide nursery areas for fish, food for waders and wildfowl and nesting sites for waders and seabirds. Stable areas that have developed over decades can be used for grazing by farm animals.

Why is saltmarsh important?

As well as creating its own unique and valuable habitat, saltmarsh can make an important contribution to coastal sea defences, with the added benefit that they are natural and economical when compared to ‘hard’ (man-made) defences. If an area of saltmarsh is large enough it can remove all of the damaging energy of an incoming wave under certain conditions.

Saltmarsh can also play an important role in climate regulation by sequestering and storing carbon. Saltmarshes are the most widespread and important of the Blue Carbon (carbon stored in coastal and marine ecosystems) habitats outside of the tropics. They can bury carbon at a greater rate, and store more carbon per unit area below-ground than their terrestrial counterparts e.g. forests (Mcleod et al., 2011); typical carbon sequestration rates in UK saltmarsh are 120-150gC m−2 yr−1 (Beaumont et al., 2014).

Saltmarsh systems are particularly important in supporting nationally and internationally important bird species, many of which are in decline. Saltmarsh habitats can provide important resources and habitat structures needed for bird breeding, wintering and migratory staging, sometimes supporting huge populations of wintering wildfowl.

There is a strong link between the natural environment and psychological well-being, including sense of self, perceived health, cognitive restoration and relief from stress. Saltmarsh plays an important part in the blue-green landscape, not only aesthetically but also in connecting people with nature and the health and well-being benefits that this can bring.

Why is saltmarsh at risk?

Saltmarsh around Chichester Harbour is believed to date back to the Bronze age when it supported the first permanent settlements. During the 18th and 19th centuries saltmarsh was viewed as having little value, areas of saltmarsh were commonly converted to agricultural and development land. More recently however, its high and unique biodiversity value and the range of functions this ecosystem carries out has become increasingly recognised. But sadly, its future is less than certain with a host of threats facing it from nature and humans alike.

One of the biggest threats to saltmarsh is a process known as ‘coastal squeeze’. This is the term used to describe the loss of coastal habitats in front of sea defences. As sea level rises, saltmarsh becomes increasingly inundated and submerged by deeper seawater for longer periods of time. Whilst some areas of saltmarsh can handle inundation, the plants that help knit together the higher reaches are only able to cope with infrequent instances of inundation. Regular or sustained submersion can kill them off, removing the roots and allowing the marsh to break up. Eventually, the conditions become too extreme for saltmarsh in front of a sea defence and it dies back completely.

In the absence of a hard sea defence, saltmarsh would naturally migrate landward as sea levels rise and adapt to this increasing pressure.

Sea level rise can also potentially bring increased wave attack, leading to erosion of seaward edges of saltmarsh habitat. Wave action can fundamentally change the structure of saltmarsh, eroding and destabilising it.

A further threat is the loss of sediment supply that is required to ‘feed’ saltmarsh. The development of hard sea defences, land reclamation and dredging all cause interruptions to sediment flow which is vital for the marsh creation process.

Recreational disturbance and trampling can cause localised damage, which is why we ask all visitors to keep to identified pathways and avoid diverting from these.

Some risks are from nature itself, with invasive grasses overtaking patches of land, forcing out native species whose root systems play an important role in stabilising the mudflats. But even some of these are dying off and leaving saltmarsh bare and open to erosion.

It is clear that saltmarsh is an incredibly diverse and valuable habitat with an intricate method of re-nourishment and natural succession. Whilst Chichester Harbour has one of the largest expanses in the UK, this title comes with a significant responsibility to try and protect it.

Find out more about saltmarshes from the Wetlands and Wildfowl Trust